What if your porn use could be a roadmap to healing, not a life sentence to sexual shame or addiction?

That’s exactly what my research on over 3,800 men and women showed. I learned that there is nothing random about our use of porn or the fantasies we pursue. If we want to outgrow our involvement with pornography, we will need to identify the hidden drivers that bring us to it in the first place.

The truth is, if it weren’t a struggle with pornography use, it would be something else. All of us turn to something unhealthy to comfort and reinforce unaddressed pain. We also do things in committed relationships to hurt the ones we claim to love the most. If our lives and marriages are doing what they are supposed to do, they will expose things about us that, under normal circumstances, we would never want to acknowledge. Confronting difficult things about who we are is how we mature. It also happens to be how we outgrow unwanted sexual behavior such as pornography use.

The Four Triggers

Through my research and therapeutic practice, I’ve discovered four triggers behind every pornography problem: purposelessness, pain, anger, and shame. Although those words may conjure up some form of immediate familiarity, I promise you that after seeing what my research revealed, you’re preconceived notions will give way to fresh understanding. Contrary to what we often conclude, a pornography struggle is not a random issue in someone’s life. Too many people falsely conclude that either they are more broken and morally corrupt than their peers, or pornography is something that everybody uses and therefore there’s no point understanding what might uniquely be luring them to it. Either option blinds us to the influence of the four drivers. If you want to outgrow your use of pornography, figure out to what extent the drivers are influencing your use of it. This article will guide you to do just that. By the end of it, you will learn how these four hidden drivers of a pornography problem show up and how to address them.

Let’s begin.

TRIGGER ONE: PURPOSELESSNESS

The Squatter

Several years ago, my family was moving from one rental property to another. It was the end of a long day with a completely full moving truck, when my wife remembered we’d forgotten to retrieve our baby stroller, walker, and bassinet from our basement. I was drenched in sweat and told her,

“I’ll just come back in a few days and get them.”

Three days later, I was back at our previous rental to retrieve our baby items. As I approached the front door, a very ominous feeling came over me. It felt as if someone was watching me. Something within me said, “Look up.” I looked up, and peering between old curtains was a man inside our previous home. He looked at me with intimidation and mouthed the words that essentially said, “Don’t come in here.” I froze. Either I could confront this squatter and risk my life, or I could forget about the baby items, as they were bound to go to Goodwill anyway. I chose to leave the squatter undisturbed.

As I drove off that day, what struck me was that this man, within three days, knew that nobody was home. He knew what to look for and took over our vacant home. Pornography is one of the great squatters of our day. When purposelessness becomes our core experience, the presence of squatters is assured.

How Purposelessness Binds Us to Pornography

When Peyton first came to my therapy office, he had the sense that his life and sexual behavior were rapidly spinning out of control. He had been referred to me by his doctor. He sought testing for a sexually transmitted infection after a series of unprotected sexual encounters. Fortunately for Peyton, his results were negative, but for the first time in his life, he realized that his unwanted sexual behavior had become unmanageable. As time went on, his sexual struggles intensified. He cared less and less for the things that are central to a healthy and balanced life: one’s body, relationships, and career.

In our second session, I asked Peyton if he had any idea what might be fueling his behavior. He disclosed that he had been recently passed up for a position for which he assumed he was the front-runner. Also, that same week, his boss told him that his year-end bonus would be 50 percent lower than anticipated. In an instant, his view of his life and career as following a smooth, upward-bending arc was crushed. His sudden change of fortune was not only immensely disappointing in terms of his career and paying off his debt from the previous year, but it highlighted how empty his life had become.

That week Peyton binged excessively on pornography. Completely consumed in self-hatred, he felt himself spiral downward. With mockery, he said to himself, Porn is the only place I can effectively get what I want. It was in that moment that Peyton began fantasizing about swiping through dating apps to use women for sexual gain. Pornography wasn’t enough—he wanted more.

Engaging Our Purposelessness

Although a man’s involvement with porn doesn’t always lead to reckless and exploitive hookups, one of the most powerful associations in my research study was between pornography use and purposelessness. In fact, the greater the experience of purposelessness, the more likely people were to increase their use of pornography. Men were seven times more likely to escalate their pornography use when they did not have a clear sense of purpose. Such men reported futility in their professional lives and had personal lives rife with disappointment. The more purposelessness some feels, the more pornography he or she will watch.

It’s crucial to understand the implications of this hidden driver. You cannot hope to overcome unwanted pornography use unless you have a plan to engage your lack of purpose. Pornography use does not happen in isolation from other parts of your life. If not for pornography, how else would you address feelings of futility? Pornography will be there for you in sickness and in health. When a romantic relationship is full of strife or emptiness, pornography accepts you and offers you fullness, for a moment. When you’re checked out at work due to years of being uninspired, pornography is far more appealing to return to after a lunch break. When you scroll through social media late on a Friday night and find yourself envious of the weekend plans of friends, pornography lets you get a version of what you want without risk or having to ask for it. The problem is that so many of us attempt to say no to porn while doing next to nothing to transform the feelings of purposelessness driving us to it.

What Google Knows About Our Porn Use

Thanks to Google Analytics, we can now track porn use in relation to specific cultural (in this case, sports-related) events. A prime example of this relationship would be the 2017 NBA Finals between the Cleveland Cavaliers and the Golden State Warriors. According to the data gained by one popular porn site, pornography use in the San Francisco Bay Area dropped 21 percent below normal when it appeared that the Warriors were going to win the championship. Once the game was over, usage numbers returned to usual.

Predictably, Cleveland’s numbers showed the opposite relationship, with porn use climbing to a staggering 28 percent over normal levels when the Cavaliers had lost the NBA Finals. Although there are a number of variables here, we can make a pretty safe assumption from the analytics data that the sports fans and porn users were representative of the same demographic. Given that assumption, it becomes clear that the role of disappointment had a dramatic impact on Cavs fans. If pornography use is shaped by the disappointment we feel even with our favorite pastimes, imagine its profound impact on areas of our of life where disappointment has more power, such as our careers and significant relationships.

No Boxing Gloves Required

Resisting the draw toward pornography doesn’t require you to get a pair of boxing gloves and steel yourself for a heavyweight slugfest against it. Not only do such shame and aversion-based methods rarely work, but they compound the problem by blinding us to the underlying issues that are causing us to turn to porn. If we have not already realized these issues, exclusively fighting against porn leaves us feeling humiliated in defeat. But when we have the integrity to go beneath the surface to find what is driving our pornography use, the purposelessness of our lives will be revealed. Rather than fighting our arousal and sexual shame, we can let our pornography struggles motivate us to find greater meaning. If you are really determined to fight something, put that spirit to good use by fighting to find purpose.

The Madness of Compulsive Pornography Use

As we have seen in the case of Peyton and Google’s data analytics, purposelessness is a powerful driver of pornography use. Using pornography appeals to people who lack purpose because it gives them the ability to get what they want, exactly when they want it. Nothing else in the world gives purposeless people more of a sense of power than pornography. But once you take its bait, you find yourself hooked into an even greater experience of futility. The madness of pornography use is that the very thing we pursue to assuage problems ends up intensifying them.

It’s common to view our pornography use as evidence for how futile and shallow our lives have become. While I understand this perspective, it will eventually rot us to the core if we stay there. Instead, allow your pornography struggle to motivate you to kick the squatters out. When they’re gone, the clarity and resolve you’ll experience will grow into greater confidence and accomplishments.

Although goals and clear planning influence us to pursue greater purpose in our lives, we also need to engage the stories of pain that drive us to pornography in the first place. Just as we learned that pornography can offer a temporary antidote to purposelessness, we also learned that it could provide a powerful antidote to pain. Yes, infants cry and (hopefully) receive nurture and comfort from a parent, but older children and adolescents learn to be quieter and increasingly self-reliant when they encounter pain. In our pain, we discover that leaning on certain behavior and substances can initially offer us a remedy to all that pain.

TRIGGER TWO: PAIN

My Crash

One summer, I made a goal to commute to and from work using only my road bike for transportation. I made it through June, July, and almost all of August. In late August, I was stopped at a red light in a bike lane. When the light turned green, I tried to propel my right pedal forward. The chain didn’t move. Two options flashed across my mind. One was to get off my bike and investigate the issue. The second was to try to jerk the pedal forward, hoping the mechanical problem was just a fluke. I chose the latter option, and seconds later my body met concrete. I looked up to dozens of concerned faces at a busy intersection. With adrenaline pumping, I hopped back up. A woman with kind eyes came into the street from the sidewalk asking, “Are you sure you are okay? That was a really hard fall.” In my embarrassment, I downplayed her worry. “Yeah. I just can’t figure out why my chain didn’t move.” The woman was not deterred and scanned my body, staring at my left leg. She said, “You are bleeding really badly. Can I get you some first aid?” I dismissed her again. “Thank you—I appreciate that. But I am just a few blocks from my office. I’ll get it cleaned up there.” I walked down the sidewalk with the confidence only a deeply wounded and proud man could display. Blood poured down my leg for four city blocks, saturating my left sock and changing the color of my shoe to burgundy.

Three months later, my skin on my leg had scarred over. The more significant issue, however, proved to be a sharp pain in my left hand. It wasn’t until a week after my fall that I realized that the most obvious wound was eclipsing the more serious concern. The pain in my hand demanded that I reexamine the story I had told about the fall. It wasn’t that I just gashed my left leg. The majority of my two-hundred-pound body had fallen from two feet high onto my left hand. The pain in my hand outlasted all other suffering from the fall. I tried ibuprofen. I tried gin and tonic. I tried pushing through it. I tried to let time heal all wounds. The pain endured. How often do our efforts to stop the pain fail to address the origins of that pain?

Locating Where the Pain Began

When we’re struggling with a pornography problem, the pain that is often at the forefront of our minds is our shame and failure. In the same way I thought my left leg was the only problem, we spend most of our efforts attempting to divert the gaze of others from our shame rather than investigating what else might be involved beyond the obvious issue. This is why the solutions we come up with involve largely superficial attempts to avoid shame, manage triggers, make New Year’s resolutions to outgrow pornography, or eventually resign to the reality that pornography will just be one struggle that will accompany us through life. And as many people have told me, it’s when I try to resist it that my desire for it intensifies.

As you can see, we try to stop our use of pornography rather than go back to the origins of when and why we learned to use it. The reason most attempts to quit pornography fail is that we don’t know what else to do when confronted with difficulty. In this way, a pornography struggle isn’t just telling us about our potential for hypocrisy or secrecy; it’s revealing how we’ve learned to interact with pain. Freedom is indeed possible, but not apart from recognizing how pornography has formed a vicious cycle that both comforts and reinforces our hurting.

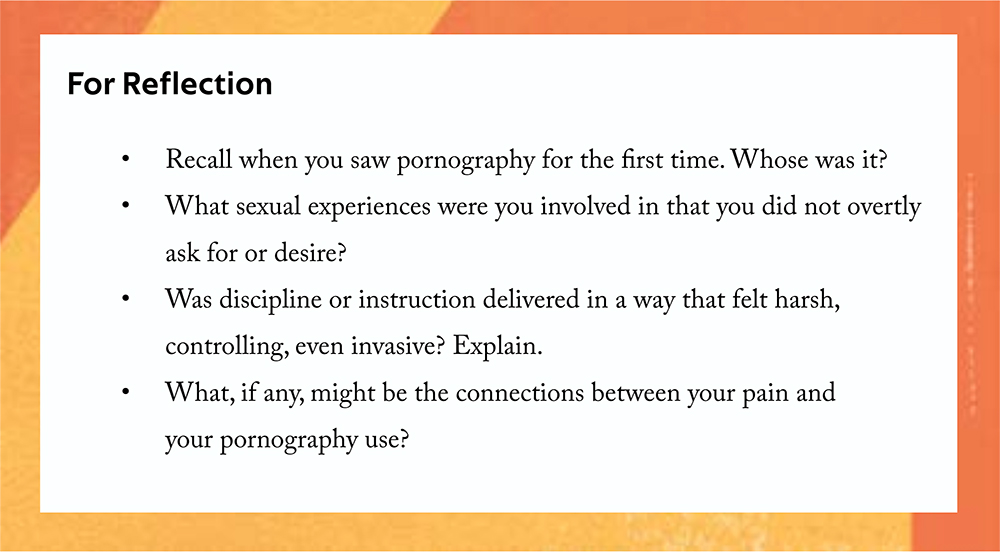

None of us escapes childhood without pain. An aggressive and intimidating father, sexual abuse, the death of a family member, being asked to play a surrogate spouse role in the breakdown of your parents’ marriage, classmates mocking your body or fashion, and systemic community violence such as racism are all examples of what we undergo. In our pain, we look for behavior and substances that provide comfort. But almost anything we lean on for support becomes the very thing that leads us further into pain. In my research, I found two types of childhood pain that consistently influenced unwanted sexual behavior: sexual abuse and the rigidity of a parent. Let’s explore how both sources of childhood pain go on to drive a problem with pornography.

Childhood Sexual Abuse

The most significant pornography users in my survey had sexual abuse scores that were nearly 24 percent higher than those who did not view pornography at all. Many people will spend their lifetimes attempting to quit porn but rarely address the harmful sexual templates established for them during experiences of sexual abuse. What you think of as isolated problems with pornography may be revealing sexual harm that’s never been addressed.

Most of us tend to see sexual abuse as inappropriate genital exposure or contact involving an adult and a child. While this is certainly true, the spectrum of abuse is actually much broader. Men and women are often surprised to learn that experiences they’ve dismissed as sexually “strange” or “kids just being kids” may also be forms of sexual abuse. Additionally, being introduced to pornography or finding a family member’s stash are often seen as rites of passage but do in fact contain dimensions of sexual abuse. Healing the harm of abuse involves recognizing the parts of your sexual story that were not explicitly chosen or consented to.

One of the many reasons sexual abuse is so damaging to us is that trust is its paradoxical foundation. The majority of victims of sexual abuse are groomed by someone close to them: a parent, sibling, neighbor, babysitter, extended-family member, or faith leader. Perpetrators of sexual abuse are attuned to the desires children have to be seen and delighted in. And they are often all too attuned to our vulnerability, positioning themselves as a kind, emotionally supportive presence. The initial relationships with the people who abused us will often feel so good, even loving, before they begin to move toward explicit sexual abuse.

In sexual abuse, the perpetrator is almost always grooming the victim to experience some degree of arousal and pleasure. It’s common for our bodies to feel aroused when we see or touch an erect penis, a vulva, or breasts, especially for the first time. And once we experience intrigue and arousal, something in us feels as though we were complicit. Once the abusers see our initial interest or intrigue, they coerce our silence with such language as “This is our little secret” or through making an overt threat.

Think about the utter madness of all this. You feel bonded to someone you initially trust, experience intrigue and pleasure but then shame, and are coerced to silence. Your body eventually needs to dissociate from the reality that any of the abuse occurred. Sexual abuse establishes a harmful sexual template in childhood, and as adults we pursue sexual experiences that mirror what we’ve come to see as normal: sex as something both pleasurable and awful.

Those who experience the pain of sexual abuse may go on to find pornography alluring for two primary reasons. One, the abuse we experienced may have involved pornography. The majority of respondents in my study did not “discover” pornography; they were introduced to it by a peer, someone older, or an adult. When this occurs, it’s common to feel not only aroused by the images but also bonded to the people showing us a whole new world. Second, pornography allows us to recreate some of the original neurochemical experiences established in sexual abuse. Pornography, like abuse, can bring about some of the initial pleasure and arousal, only to be followed by secrecy, ambivalence, and shame.

A Rigid Parent

A rigid parent has excessive rules and regulations. This parent desires control and will use emasculation or aggression to get it. This mother or father might demand compliance, but he or she is often not compliant to anyone. Common examples of having had a rigid parent involve feeling as though you grew up under considerable surveillance regarding what you watched, what you ate, or even what you thought. You were watched like a hawk, but at the same time, you had a front-row seat to their hypocrisy.

Rigid parents like to see everything as a black-or-white issue. Decisions are much easier. Even when a situation has considerable complexity, rigid parents will make dogmatic decisions that benefit themselves. One of the questions I’m often asked is “What’s the difference between a family with healthy boundaries and one that is truly rigid?” One way of thinking about that is to view healthy boundaries as being like the walls within your home. The point of these walls is to maintain structure and safety. Because of their presence, they actually expand the possibility of stability, play, and comfort within the home. The harsh and unpredictable conditions on the outside that cause chaos are guarded against. But if your home was overly full of walls, especially where there should be windows or open space, you’d feel trapped within and miss the beauty outside. People who grow up in rigid family systems do not experience the freedom of play and fun. And so when one of these people gets into normal quarrels with a sibling, makes a mistake, or shows that he or she is human in some way, the person is met with a belt, harsh word, or shaming look. To survive a rigid family, one complies or departs.

Pain Shapes Fantasy

So the question you are probably wondering is “What is the connection between rigidity and sexuality?” Well, it turns out there is a direct one. Rigid family systems shape the particular sexual fantasies and behavior that people pursue. For example, men who grow up with strict fathers are more likely to develop fantasies of power over women in the type of pornography they pursue. This includes women who are younger with smaller body types and women from another race who appeared, to them, as submissive. The implication is that sons who were powered over tended to grow up to be men who desired power over others. What this tells us is that the misuse of power self-perpetuates, generation after generation.

My research found that women who wanted to be used or have harm done to them in their sexual fantasies were two and a half times more likely to have had a strict mother. The implication was that daughters who were powered over tended to grow up to be women who pursued fantasies where harm and cruelty were reinforced. Rigid family systems will set children up to be adults who must work to reverse or repeat unhealthy power dynamics from their youth.

The key point we will address in more detail in our next section is that anger increases in rigid family systems (and also in families that were emotionally disengaged). Rigidity leads to anger because you are constantly exposed to the misuse of power of those who are supposed to use their power for your good. Pornography seems like the perfect solution to children who have unresolved pain, as it offers an opportunity to escape the misery and also provides them with a virtual world in which they have power unavailable to them in real life. Tragically, the types of pornography that appeal to us most are reenactments of the pain we know most intimately.

TRIGGER THREE: ANGER

Stifled Desire

When my son was almost two years old, my wife and I reveled in what a remarkable eater he was. He was eclectic in his tastes and could scarf down kale or kimchi as readily as he would a goldfish cracker. One day I came home with a white take-out box from a Thai restaurant, and the second he spotted the iconic white box, he literally began to dance with excitement. I placed the food on the kitchen table, and he lurked behind me. With a smile, he asked, “I have some, Daddy?” I took a piece of chicken out and offered it to him. Unexpectedly, he exploded into a rage. Overcome with anger, he fell to the floor and began pounding his little fists into the ground, screaming, “No! Tall bite! Big bite!”

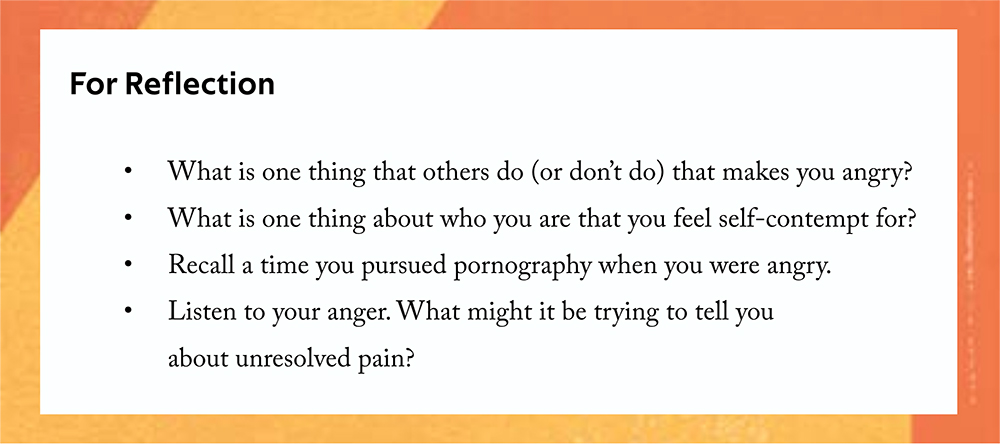

What story could be more illustrative of the fact that stifled desire can easily lead to anger? If the interplay between desire and anger is at work in the life of a two-year-old with food, I can assure you it is at work within our sexual lives as adults. One of the most sobering things I’ve needed to confront in my journey to freedom from unwanted sexual behavior was the role anger played in my pornography use and sexual life. The times I’ve used pornography the most were the times I was filled with considerable anger at myself or others, whether because of my weight, career paralysis, or the lack of sexual desire from my wife. The desires we have for inspiring work, meaningful relationships, and passionate emotional and sexual connection are all beautiful. But when they are unfulfilled, be on high alert for how anger will propel you to unwanted sexual behavior. Where there is pornography, you’ll almost always have the presence of anger at work beneath the surface of desire.

The Dignity of Anger

Before we go deep into the potential devastation that anger can cause, let me tell you that it’s not intrinsically something you need to erase from your life. Anger is like a radar that will let you know that something within you or around you is not as it should be. Anger alerts us to something we deeply care about, even if we’re going about the solution the wrong way. Be curious about what your anger is indicating, for when it is matured, it will move you to seek justice and restoration.

There’s More Than Lust Involved

There’s no denying that lust and erotic desire are important factors driving pornography consumption. But in our excessive focus on lust, we all too easily lose sight of the other contributing factors that drive our unwanted sexual behavior. One in particular that is almost always at play is anger. Consider these examples:

-

- A single man is angry when a friend neglects to invite him to a party, and he almost immediately finds

himself lusting for a hookup to override the experience of betrayal.

- A single man is angry when a friend neglects to invite him to a party, and he almost immediately finds

-

- A married man makes a bid for sex with his wife but is turned down. Hours later he can’t sleep and

“lusts” for pornography.

- A married man makes a bid for sex with his wife but is turned down. Hours later he can’t sleep and

-

- A woman feels as though her significant other doesn’t pursue her emotionally. She cheats on him

with one of his friends who is far more engaging.

- A woman feels as though her significant other doesn’t pursue her emotionally. She cheats on him

As a clinician, I have seen these dynamics more times than I can count. When these individuals talk about their experiences leading up to their choices of unwanted sexual behavior, I’ve never heard them acknowledge the role anger played. Instead they prefer to see their sexual behavior as the result of loneliness and pain. The danger of this perspective is not that it is untrue but that it is incomplete. These lust-lonely-hurt paradigms leave the other parts of the equation to fester in hiding. By failing to shed light on the underlying anger, we set ourselves up to repeatedly fail. Why? It’s simple. You cannot transform an area of your life for which you have no language to describe it. If you want to figure out why you use pornography, figure out what’s gotten you so angry.

Exclusively focusing on lust instead of recognizing anger as an equal contributor to pornography use will lead to a dramatically different outcome. The conventional wisdom is that those who struggle with pornography do so because they have unmet needs, self-medicate their stress, and need an escape from pain. The logic here is fairly simple: we are lonely and rejected and seek out porn to soothe ourselves. One man named Steve wanted to figure out why he couldn’t stop his porn use. He had tried using filtering software, but he began to see the interventions like fences that he was always trying to get over or under in order find pornography. Then a friend of his encouraged him to find a recovery community where people meet weekly and text one another when they feel triggered. All these efforts provided some added benefits to Steve’s life but were not guiding him to address what was driving his pornography use. Then one day it struck him: “If my life is one big trigger, that probably says more about me than my circumstances.” Steve disliked his body, felt as though his colleagues at work had better opportunities for advancement, and had friends who were entirely unreliable. Each time he experienced an unwanted feeling, pornography use followed. Texting a friend and filtering out pornography might have their places, but not if Steve couldn’t develop a different path forward when he felt self-contempt or anger at others. Like many, Steve wanted the conditions around him to change rather than him developing an inner life capable of moving through turbulence.

Confront Yourself, Not Someone Else

People who struggle with pornography prefer to locate their problems outside of themselves. They find themselves consistently immersed in interpersonal conflicts (with their significant others, bosses, friends, children, and so on) and become convinced that the world is conspiring against them. They wonder why people don’t do more to love them (especially after all they do for others) but reflect s0 little about how entitled they have become. You cannot experience love where there is a desire for control. If we want to outgrow a pornography problem, we need to develop integrity with not just our sexual lives but also our resentments. We need to allow our use of pornography to challenge us about the people we choose to be in the face of adversity. You will always have a “good” reason to use pornography. Change is more likely to occur if you confront yourself in adverse conditions rather than merely avoid your personal dilemma with porn.

Rather than basing your attempts to overcome pornography on blocking or stopping lust, identify what elicits your anger. Anger is nothing to be ashamed of; it is one of our greatest teachers. In the same way that your sexual fantasies have something to reveal to you, your anger can reveal a path to personal growth. In our next section, we’ll explore the final hidden driver of pornography use: shame. Although, due to religious or cultural norms, we often think of shame as an inevitable outcome of watching pornography, the reality is that the shame you have in the first place contributes to the likelihood that you will use pornography. As you’ve learned from these past three triggers, the collective experiences of unresolved purposelessness, pain, and anger tell us that there is something truly broken about who we are. With pornography, we pursue confirmation that this is indeed true.

TRIGGER FOUR: SHAME

Dough

In graduate school, I lived with a housemate who worked the closing shift at our local Starbucks. It was a diabolical gift. After work he would walk into our home with a bounty of free day-old pastries. Our kitchen counter would become a stadium of blueberry and pumpkin scones, old-fashioned and chocolate doughnuts, cinnamon rolls, molasses cookies, and the most seductive siren of all: the apple fritter. On evenings when I would get home late after a particularly difficult day, I’d hear the baked goods whisper to me, telling me to put them in the microwave for sixteen seconds and lavishly drizzle white chocolate sauce on top.

The next morning, I would wake and, unsurprisingly, despise myself. The whole day, a fried mass of sugar from the night before would hold me in contempt the following day. I’d see my belly folded over my jeans and blush at the prospect of others seeing my weight and, therefore, an appetite I had condemned. In my self-hatred, I’d hide in a coffee shop and study until it was late enough for my housemates to be in bed. After a day of shame and shame avoidance, I’d look to pastries not only for comfort but also to set up another day of judgment.

Unfortunately for me, this carbohydrate ritual of consumption, shame, and self-hatred had been going on for more than a decade. If my carbohydrate episodes were a television show, there would be a flashback to my thirteen-year-old self, an obese eighth grader in the suburbs of Washington, DC, belly bulging over discount jeans, about to fail algebra, and whose bus-stop nickname was Doughnut. I was, as my bus-stop peers would say, “too fat to even play football.” At the bus stop, several middle schoolers would laugh as one peer poked my belly, making the noise of the Pillsbury Doughboy. In the evenings, I would echo and intensify their contempt, eating sweet dough and shaking my stomach like a doormat. What was happening in graduate school was a repetition of the shame that I underwent in middle school.

The Face of Shame

When people talk to me about their use of pornography and the specifics of what they search for on the internet, they fight to keep shame from fully possessing them. They avoid eye contact, fail to finish their sentences, and become extremely evasive of questions and vague in their answers. Sometimes they even stop talking altogether. Their faces become red, their eyes search in hypervigilance, and if the experience intensifies, their bodies hunch over, their heads droop, and they bury their faces in their hands. Shame is primarily concerned with the eyes or the perceived gaze of someone seeing our unwanted behavior. Shame makes us want to hide. It tells us that something about us is beyond repair or intrinsically foul and we would be better off unseen. Our discomfort is unbearable. All we can do is run from how widespread our problems seem to be.

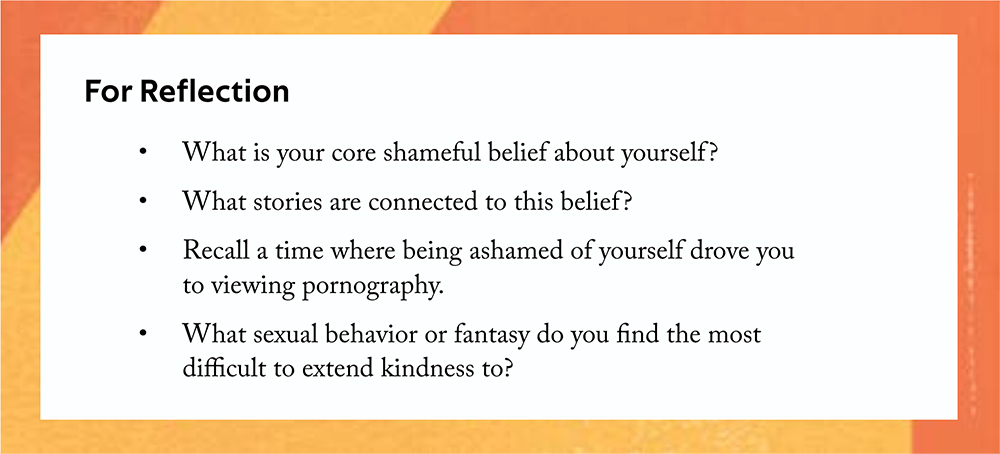

For those of us who have struggled with pornography or other unwanted sexual behavior, shame is an all-too-familiar companion. Given this, it might seem unnecessary to point out the relationship between shame and pornography. Surely, feeling unworthy after having done something sexually is a fairly straightforward affair: we’ve done something wrong and now we feel ashamed of it. However, when we pause to look more closely at the relationship between shame and pornography use, something surprising comes to light: our shame isn’t simply a natural consequence to viewing pornography; it’s also a key driver propelling us to it.

According to the data from my research, men were almost 300 times more likely to seek out pornography for every unit of shame they felt about such behavior. For women, the numbers were almost double, with those in my sample being 546 times as likely to do so. These numbers represent hard data that anecdotal and personal experiences alone can’t validate: our shame, not pleasure, drives pornography use.

At some point in our lives, we’re going to have to engage the stories that shame is telling about us. Do you believe you are not good enough? Too insecure? Too awkward? Too stupid? An intrusion? Whatever your core belief about yourself is, be on alert for how you will manufacture evidence to confirm that belief. Within your shame are clues into the stories that convinced you that you were unwanted in the first place. Those stories, not the shame of pornography use, are the most crucial to address.

The next time you feel shame about something such as your body or your latest pornography consumption, I’d invite you to go deeper into what exactly you believe about yourself. Let me show you three brief examples of how a core belief shapes your experience of shame. Let’s say your core belief is “I am unlovable.” Your shame will tell you that if someone got to know the real you, he or she would not love you. If your core belief is “I am insignificant,” your shame might tell you that you look at porn as a consolation because no real romantic partner would ever be interested in someone like you. Or if you believe, “I am screwed up,” because you were aroused by something you thought you shouldn’t have been aroused by, your shame will use your latest escalation in pornographic themes as evidence of how messed up you are. Pornography use is just the icing on the cake of shame.

Facing Shame

Now that we’ve established that shame drives pornography use, how do we begin to reduce its power? Believe it or not, the Discovery Channel’s Shark Week holds a clue for how we can disarm and, eventually, overcome our unwanted sexual behavior. In my book Unwanted: How Sexual Brokenness Reveals Our way to Healing, I discuss an interview with Andy Casagrande, the cameraman responsible for the harrowing and death-defying footage of aggressive and large great white sharks. Casagrande was asked what in the world he does when one of these behemoths is swimming right at him. His surprising answer was that he has to do something completely unexpected: swim straight for the shark with his camera. Swimming toward the shark seems to trigger an instinctual defensive reaction in the sharks. According to Casagrande, “The reality is that if you don’t act like prey, they won’t treat you like prey.”

So what does swimming with terrifying sharks have to do with our shame? Simply this: we need to face it. The experience of shame is the apex predator of our lives, and our impulse to evade our “great white” memories will only set us up for lifetimes of living as prey to shame’s accusations. Just as a shark swims away when challenged, the power of shame is disarmed when we confront it, not flee from it.

Disarming Shame

The core beliefs we hold about ourselves (those toxic beliefs that we’re not worthy of love or belonging)are not random. They are direct reflections of the stories we’ve encountered in life. When I was first intentionally addressing my problems with pornography, I realized that my core belief was that my desires were defective and untrustworthy. After all, my desires led me to obesity and pornography. I thought the solution was somehow to lessen my desire in order to mitigate future damage. But when I went back to the stories of my desire from childhood, I saw a six-year-old boy who used to get so excited about a barbecue that he’d have a bowel movement and bellow out songs about his love for hamburgers from the toilet. I saw a kid with a beautiful desire to learn about sex and pleasure against the backdrop of a family and religious community that was almost completely silent. Healing was not about arresting desire but about setting it free. Our shame exposes not only our failure but also the things that are the most beautiful about us.

One day of deliberately facing your shame with curiosity and kindness will lead you into greater transformation than will a decade of willpower and self-control techniques. If self-hatred is the key driver of unwanted pornography use, kindness is its kryptonite. Shame does not need to have the last word. It can actually be the very experience that invites you to dramatically reorient your life around kindness. When individuals change their unhealthy patterns of interacting with their shame, their behavior changes.

CONCLUSION

I hope this article has shown you that your pornography struggle can be a road map to healing. Rather than focus all your efforts on trying to resist using pornography, you were invited to consider a radically different perspective: the keys to the freedom you seek are embedded within your pornography use. Pornography use can be evidence of shame, but it can also provide you with clues about pursuing healing and flourishing in your life.

As you can imagine, the journey ahead of you has just begun. And although that may seem daunting, what I can promise you is that your willingness to walk the path ahead will lead you to a holistic transformation you never could have imagined. As you consider the next steps on your journey, I would recommend three actions: searching for meaning, pursuing holistic transformation, and journeying with others.

1. Searching for Meaning

Your use of pornography has so much to teach you, if you are willing to pay attention. Rather than trying to stop pornography use, search for the meaning embedded within it.

Something I often get asked by people struggling with pornography use is “How bad of an issue is this for me? Should I even be concerned?” My guess is that if you are asking those questions, something inside you already knows that your relationship to pornography is negatively affecting you. The first question many people get stuck on when deciding to pursue significant change is “Where do I even start?” If that’s a question you are wrestling with, you aren’t alone. Or perhaps you’re someone who has struggled with pornography use for a very long time but without much progress toward the freedom you desire. The question you may be facing is “Why should I even bother trying anymore?” You too aren’t alone in the fear of taking another step toward hope when you’ve become accustomed to disappointment.

So I’ve made that first step just a bit easier. The Sexual Behavior Assessment will help you get a better grasp of the meaning of your pornography use, what sustains it, and where your struggle may have originated. The Sexual Behavior Self-Assessment is designed to help you identify themes in your life that contribute to your unwanted sexual choices. The assessment will show you the primary predictors in your story—past and present—that could be influencing your behavior. Until these dimensions of your life are transformed, the struggle with pornography will often remain. This assessment is also included in the online course I offer. Find out more about the self-assessment at sexualbehaviorassessment.com.

2. Pursuing Holistic Transformation

When focusing on outgrowing your use of pornography, it’s essential that you pursue transformation across multiple areas of your life. As you’ve learned, even if you could stop using pornography for a year, it would not resolve the purposelessness you’re experiencing in your career or marriage or social life. In the same way, going back to school or seeing a career coach are beneficial for vocational development but do little to heal childhood pain that drives you to toxic sources of comfort. Very rarely will you find a community that offers a one-stop shop for all areas of transformation. All this means is that you will need to find the appropriate community for each stage of personal growth. What you should consider right now is not how to address all hidden drivers of your pornography use but rather the one or two drivers that really jumped out at you as you read this article. In moving forward, consider these questions:

• One key driver of my pornography use I feel most ready to engage is:

_____________________________________________________________

• Starting today, one way I will engage this area of my life is by:

_____________________________________________________________

• The resources (money, time, and so on) I will need to make this happen are:

_____________________________________________________________

• Instead of just thinking about being free from porn, this is what I want to be

free for: ______________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

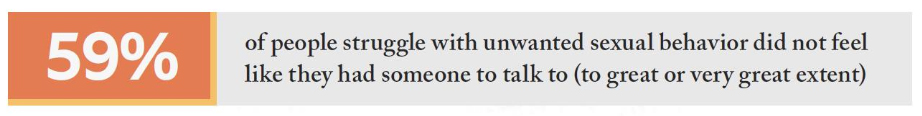

3. Journeying with Others

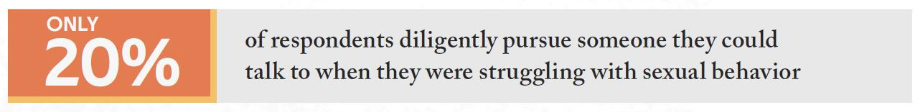

My research showed that journeying with others is a beneficial yet tremendously under-pursued decision for people struggling with pornography. Consider these findings:

As you can see, most people who use pornography struggle in the shadows. Isolation in the short term protects us from our natural fear of exposure. But that exposure is what we most need, because in the long run, we live as prey to the voice of shame when we struggle alone. Unintentionally, when we ignore care or our struggles, we severely stunt our personal development. Like a cavity in a tooth, we can either address the problem now or incur increased pain and expense later.

My research showed that when people pursued someone to talk to, they saw a 22 percent reduction in significant pornography use. One of the greatest gifts you will discover is that by sharing your story, you can be loved more, not less, in the telling of it. At the same time, although talking with an ally (a friend or fellow sojourner) about a personal struggle is beneficial, more is needed to help people completely outgrow their use of pornography.

For those of you who read this article to familiarize yourselves with these concepts, I hope doing so has led you to a greater understanding of the origins of your pornography use. But for those of you who feel you want to go further beyond the basic accountability partnership, I have more for you. The reason most accountability falls short in helping people outgrow pornography use is that it’s often done without deep engagement with the four drivers we discussed in this article. Too many have arrived in my office having tried multiple attempts, often over years, to end their unwanted sexual behavior. So when I finished the research and writing of Unwanted, I had to make sure those folks believed that one more attempt would be worth it.

3 RESOURCES FOR YOUR PATH TO FREEDOM

Some of you might be accurately wondering how an article might really address an issue that has plagued you for decades and led to countless hours of anguish or even the end of significant relationships. Truth be told, this article will not cure you. But what it can do is direct you on a completely different path than you likely would have ever considered. Just as our involvement with pornography is not random, the path to freedom is not either. These resources are designed to help you identify and transform the specific triggers in your life:

-

-

- Resource 1: My recently released book, Unwanted: How Sexual Brokenness Reveals Our Way to Healing, is the result of the multi-year research project on over 3,800 men and women that I mentioned earlier. It’s a faith-based work that invites you to consider three core questions: “How did I get here?” “Why do I stay?” and “How do I get out of here?

-

-

-

-

- Resource 2: If you want to know how your story (past and present) is shaping your sexual choices right now, my cutting-edge self-assessment tool will show you the key drivers of your unwanted sexual behavior. Lots of assessments will tell you if you have a “problem” with pornography, but chances are that if you’re taking a quiz, you already suspect you have one. The Sexual Behavior Assessment will take you many steps further. It will show you the why behind your unwanted sexual choices. Go to www.SexualBehaviorAssessment.com for more information.

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Resource 3: If you want it all, you can use my five-month e-course, The Journey, as a self-study or small-group study. Through more than eighteen episodes, in-depth assignments built around the Sexual Behavior Self-Assessment, and a closed Facebook group, you will learn to identify and transform the areas of your life that contribute to your unwanted behavior. The Journey course is only $24.99 per month so anyone can begin their path to freedom from sexual brokenness. You can learn more at www.TheJourneyCourse.com. Go as deep and as far as you would like to go. Watch a free sample episode at www.thejourneycourse.com For your courage to begin this journey, you have my full respect. Allowing your pornography struggle to show you the path to healing is one of the most counter-intuitive but generative decisions you can make.

-

-

-

FREE GIFT

As a thank-you for reading this article, I’m pleased to offer the Sexual Behavior Self-Assessment free of charge (a $19.97 value) for a limited time. Visit SexualBehaviorAssessment.com to redeem your free access.

Freedom is closer than you think.

About the author:

Jay Stringer is a licensed mental health counselor and ordained minister. Jay’s award-winning book Unwanted was based on research on nearly 4,000 people struggling with unwanted sexual behaviors like the use of pornography, extra-marital affairs, and buying sex.

Stringer holds a Masters of Divinity and Masters in Counseling Psychology from the Seattle School of Theology and Psychology and received post-graduate training under Dr. Dan Allender while serving as a Senior Fellow at the Allender Center. Jay lives in Seattle, WA with his wife and two children. To learn more about Jay visit his website at www.jay-stringer.com.

Copyright © 2020 by Jay Stringer. All rights reserved.

Much of this article is adapted from Unwanted, by Jay Stringer. Copyright © 2018. Used by permission of NavPress. All rights reserved. Represented by Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. Some of the anecdotal illustrations in this article are composites of real situations, and any resemblance to people living or dead is purely coincidental.